Crossing Boundaries: Learning Design and Work-Integrated Learning

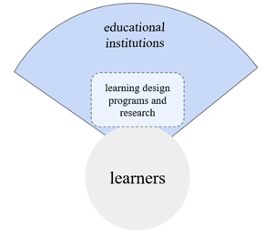

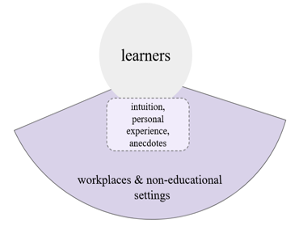

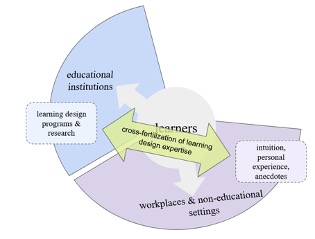

Learning design programs and research often focus on the work done within educational institutions, particularly post-secondary institutions (Figure 1). As a result, the models and practices associated with work-integrated learning have been overlooked. Instead, the practice of learning design within workplace settings is instead often guided by intuition, personal experience, and anecdotes (Giacumo & Breman, 2021) (Figure 2).

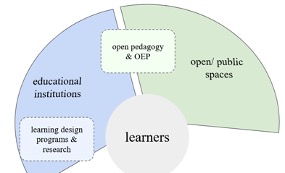

At the same time, Open Educational Practices (OEP) is an emerging area of interest among learning designers. They “consist not only of creating and reusing OER, but also of other forms of transparency around academic practice, such as blogging, tweeting, presenting, and debating scholarly and pedagogic activities, in ways that promote reflection, reusability, revision, and collaboration” (Havemann, 2016, p. 7). As a result, they have often focused on drawing learners and learning design expertise into open and public spaces, using Open Educational Resources (OER) as a starting point (Figure 3).

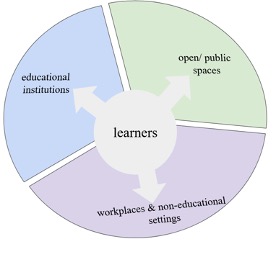

However, with roots that can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s, early open pedagogy emphasized the importance of negotiating the tensions between individual and community needs rather than sharing in open and public spaces (Paquette 1972/ 2005). Echos of these ideas can now be seen emerging among contemporary open pedagogues. DeRosa and Robison (2015), for example, suggested that open pedagogy involves “remaking our courses so that they become not just repositories for content, but platforms for learning, collaboration, and engagement with the world outside the classroom” (p. 118). Tur et al. (2020) further suggested that open educators are committed to “opening up of the whole teaching and learning process from design to implementation and assessment with all the implications and possibilities for educational transformation that may ensue” (p. 11), and Elias (2021a) found that open educators were often motivated by the desire to extend learning beyond the confines of the course. Extending on these ideas, I suggest that there is a need not only to consider the ways in which opening might be imagined not only in terms of access, but also in terms of crossing the boundaries between what it means to learn in school, at work and beyond (Elias, 2021b) (Figure 4).

Within workplace settings interesting work is underway relating to topics including problem-based and scenario-based learning, virtual training and simulations, authentic assessment and the measurement of learning impact (Abaci & Pershing, 2017).

Learning designers working in business and industry regularly conduct needs analyses, develop eLearning and adapt designs for different cultures, regions and audiences (ATD et al., 2015). Beyond teaching technical skills, work-based learning designers are increasingly being asked to develop performance supports and just-in-time training that enables enhanced knowledge sharing and generation through collaboration in order to address increasingly complex and ill-formed problems. Moreover, learning designers working in these settings often work in teams developing both instructional and non-instructional learning solutions (Molenda & Pershing, 2004). Giacumo and Breman (2021) found that learning practitioners in workplace settings were significantly more likely to employ agile and rapid prototyping approaches to learning design as well as performance gap analyses.

Expanding our definitions of open pedagogy and OEP to include the crossing of boundaries into non-educational settings has the potential to benefit both learning design practitioners and the learners that they support. For example, an approach in which business managers, academics and practitioners equally exchange and test ideas has tremendous potential to enable cross-fertilization of ideas and practices and challenge learning designers to further extend their ideas of openness, even if these activities do not take place in open/public spaces (Figure 5).

Continuous Learning

We often describe the role of the learning designer as one that involves supporting our learners and those learners are continuously moving between and through educational and non-educational spaces.

Those learners are continuously moving between and through educational and non-educational spaces. Keeping in mind that we are working with the same learners, I challenge emerging practitioners to critically consider:

- What is different about learning that takes place outside of formal educational settings? What are the benefits of those differences and for whom?

- Why might approaches to learning design diverge outside of educational settings?

- How learners might benefit if learning practitioners more openly exchange ideas, practices and experience between educational institutions and non-educational settings in increasingly intentional ways?

- How might expanding the definitions of open pedagogy and OEP affect our approaches to learning design?

References

Abaci, S., & Pershing, J. A. (2017). Research and theory as necessary tools for organizational training and performance improvement practitioners. TechTrends, 61(1), 19-25.

ATD, IACET, & Rothwell & Associates. (2015). Skills, challenges, and trends, in instructional design. [White paper]. ATD Research: Connecting Research to Performance Whitepaper. https://www.iacet.org/default/assets/File/pdfs/2015%20ATD_

Research_Skills_Challenges_and_Trends_in_Instructional_Design.pd

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5), 15-34.

DeRosa, R., & Robison, S. (2015). Pedagogy, technology, and the example of open educational resources. EDUCAUSE Review. http://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/11/pedagogy-technology-and-the-example-of-open-educational-resources

Elias, T. (2021a). “A situation of open education”: Using collaborative relational mapping to explore motivations and constraint among open educators. Journal of Interactive Media in Education

Elias, T. (2021b). Embracing Entanglements: Exploring possibilities of non-traditional scholarship. In S. M. Morris, L. Rai and K. Littleton (Eds), Voices in Practice: Narrative Scholarship in the Margins

Giacumo, L. A., & Breman, J. (2021). Trends and implications of models, frameworks, and approaches used by instructional designers in workplace learning and performance improvement. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 34(2), 131-170.

Havemann, L. (2016). Open educational resources. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of educational philosophy and theory (pp. 1–7). Springer.

Koseoglu, S., & Bozkurt, A. (2018). An exploratory literature review on open educational practices. Distance Education, 39(4), 441-461.

Molenda, M., & Pershing, J. A. (2004). The strategic impact model: An integrative approach to performance improvement and instructional systems design. TechTrends, 48(2), 26-33.

Paquette, C. (1979). Quelques fondements d’une pédagogie ouverte (T. Morgan, Trans., 2017). Québec français 36, 20–21. https://homonym.ca/?s=paquette

Paquette, C. (2005). La pédagogie ouverte et interactive: une brève histoire. Ecole Arc-en-ciel. http://arc-en-ciel.csdm.ca/files/Pedagogie-ouverte-et-interactive.pdf

Tur, G., Havemann, L., Marsh, D., Keefer, J. M., & Nascimbeni, F. (2020). Becoming an open educator: Towards an open threshold framework. Research in Learning Technology, 28, 1-15.